Threat Assessment and Prioritization of High-Value Medicinal Plants in Pindari Valley, Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, India

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.16.1.24

Copy the following to cite this article:

Kumar R, Arya D, Sekar K. C, Bisht M. Threat Assessment and Prioritization of High-Value Medicinal Plants in Pindari Valley, Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, India. Curr World Environ 2021;16(1). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.16.1.24

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Kumar R, Arya D, Sekar K. C, Bisht M. Threat Assessment and Prioritization of High-Value Medicinal Plants in Pindari Valley, Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, India. Curr World Environ 2021;16(1). Available From : https://bit.ly/3urRltQ

Download article (pdf)

Citation Manager

Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Publishing History

| Received: | 17-07-2020 |

|---|---|

| Accepted: | 22-02-2021 |

| Reviewed by: |

Tatiana Shupova

Tatiana Shupova

|

| Second Review by: |

Ghulam Mujtaba Shah

Ghulam Mujtaba Shah

|

| Final Approval by: | Dr. Hemant Kumar |

Introduction

The mighty Himalaya contains a plentitude of medicinal plants and its habitants possess the knowledge of traditional medicinal plants. Indian Himalaya region (IHR) harbors about 1748 (23.4% of India) plant species recognized for their medicinal values. The higher diversity of medicinal plants in IHR is represented by the occurrence of a variety of native (31%), endemic (15.5%) and threatened elements (14% of total Red Data Book plants of IHR).1The need of medicinal plants is continuously increasing at local and global levels. Due to the high demand of medicinal plants in the Himalayan region, about 90% are collected from the wild2 and around 70% are unscientifically harvested/extracted from wild which enhances the loss on medicinal plant diversity.2, 3

Ever increasing demand of medicinal plants along with the habitat destruction, the world is experiences the principal challenge of minimizing loss of biodiversity 4,5 by conservation efforts. Further, few conservationists have tried prioritization of conservation efforts6,7 due to higher number of extinction rate.8,9 Number of medicinal plant species is now described under different threat categories10 and in the immediate future, many species may warrant the declaration of a threatened status until adequate scientific data are available.11 Therefore, the key challenge in the sustainability of medicinal plants is to synthesize the data on availability of medicinal plants and prioritization of certain species that require immediate conservation action.12,13,14,15 A number of studies have been conducted on the utilization of medicinal plants in the IHR , viz, Dhar et al.,3, Bisht et al.,14, Kala16,17, Gaur18, Maikhuri et al.,19, Chandra Sekar and Srivastava20, Chandra Sekar and Rawat21, Negi et al.,22 Bisht et al.,23 Joshi and Chandra Sekar24 Joshi et al.,25. However, the Pindari region is not having the data-set on diversity of medicinal plants, utilization and conservation efforts. In view of above, we studied the diversity of medicinal plants in Pindari Valley, a buffer zone region of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, Uttarakhand.

Objectives of the Study

Keeping all the above in mind and the high use value and conservation importance of medicinal plants, the present attempt has been made to: (i) prepare an inventory of locally occurring medicinal plants through primary survey and secondary literature sources; (ii) identify and score the threatened and high-value medicinal plants (THMPs) based on their ecological (habitat, nativity, endemism and threat status) and socioeconomic values (plant part used, use value, user group and extraction trend); (iii) Prioritize the threatened high-value medicinal plants; (iv) suggest sustainable utilization and conservation strategies for the THMPs.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

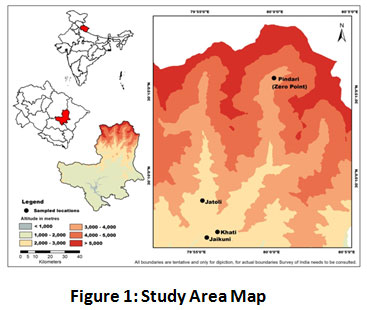

Pindari Valley (a buffer zone of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve) is situated in the Bageshwar district of Uttarakhand, Western Himalaya (Figure 1). The total area of the Park is 339.39 km2at latitude 30° 15’ N and longitude 79° 13’ to 80° 02’ E. It lies between the Nanda Devi and Nandakot peaks and the presence of glacier extends from 3600 to 5000 m. The Pindar Valley is named after the Pindar river which emerges from the Pindari Glacier. The valley remains completely covered with snow for six months (early October to March). The entire valley has been considered for documentation of medicinal plant diversity. People traditionally collecting the medicinal plants from the valley resurveyed for recording the presence of medicinal plants. Further, the similar habitats nearby the traditional collection area were also surveyed for getting additional information on availability.

|

Figure 1: Study Area Map. Click here to view Figure |

Questionnaire Survey/ Interviews

A semi-structured questionnaire survey was conducted in two villages namely, Jaitoli and Khati of Pindari Valley in the years 2016-2018 (Figure 1). A total of 42 informants were selected randomly from 32 households for obtaining the utilization patterns. Further, the informants and Vaidyas (Medicine men) were also accompanied in the field for correct identification of particular plants, apart from house-hold interview. The complete information on medicinal plants, i.e., parts used and their habitat were collected. The information further cross checked with elderly people / Vaidyas repeatedly for confirming the utilization patterns.

An Approach for Rapid Threat Assessment (RTA) and Prioritization

For threat assessment, a list of Threatened and High-value Medicinal Plants (THMPs) was developed and rapid threat assessment (RTA) was carried out using Rapid Vulnerability Assessment method followed by Cunningham26, and has been employed successfully by Shrestha and Shrestha27 and Pandey et al.,28. We followed an analytical method to prioritize the species of THMPs based on globally standardized criteria. To assess each species, we have used a total of seven ecological & socioeconomic criteria (i.e., habitat, plant part used, use value, user group, extraction trend, nativity, endemism and threat status). An appropriate numerical score ranging from 1 to 4 was assigned to each of these criteria (1 for low and 4 for high threat)13,26,29. The prioritized species were based on the sum of the scores assigned to each of these criteria (Table 1) as explained in Box 1.

Box 1: Criteria Used and their Detailed Explanation.

|

(1) Habitat: Habitat of the species was assessed on the basis of field observation during the field surveys and species were scored for the above mentioned four categories. Habitats like gravel, rocky and stony slopes are very fragile, species in these habitats were considered vulnerable to even the slightest human intervention and therefore scored at 4 (high threat). While, species in grasslands, alpine pastures and open/alpine slopes were ranked least vulnerable (score 1) as they have a large habitat range. |

Table 1: Threat Assessment Criteria, Categories and Assigned Scores for High-Value Medicinal Plants of Pindari Valley (see Materials and methods for detailed explanation)

|

S. No. |

Criteria |

Category |

Score |

|

|

Habitat |

(a)- Gravel/soil, boulder stony/rocky slopes (b)- Moist, marshy, shady, glacial moraine land (c)- Riverine, shrubberies, riverbeds (d)- Grasslands/ alpine pastures, open/alpine slopes |

4 3 2 1 |

|

|

Parts used |

(a)- Whole plant (both underground and aerial portions) (b)- Underground portions (Roots/Rhizomes/tubers) (c)- Bark, stems, fruits, flowers, bulbs, seeds (d)- Leaves, resin, latex |

4 3 2 1 |

|

|

Use value |

(a)- More than 6 uses (b)- 4-5 uses (c)- 2-3 uses (d)- 1 use |

4 3 2 1 |

|

|

User group |

(a)- Local people + local exchange + trade (b)- Local people + trade (c)- Local people+ local exchange (d)- Local people |

4 3 2 1 |

|

|

Extraction trend |

(a)- Commercial + self (b)- Commercial (c)- Self-use (d)- No use |

4 3 2 1 |

|

|

Nativity/ Endemism |

(a)- Native/endemic to India (b)- Native/endemic to Himalaya (c)- Native/endemic to Himalaya and surrounding countries (d)- Cosmopolitan |

4 3 2 1 |

|

|

Threat status |

(a)- Status in 3 categories or more (b)- Status in 2 categories (c)- Status in 1 category (d)- Not assigned |

3 2 1 0 |

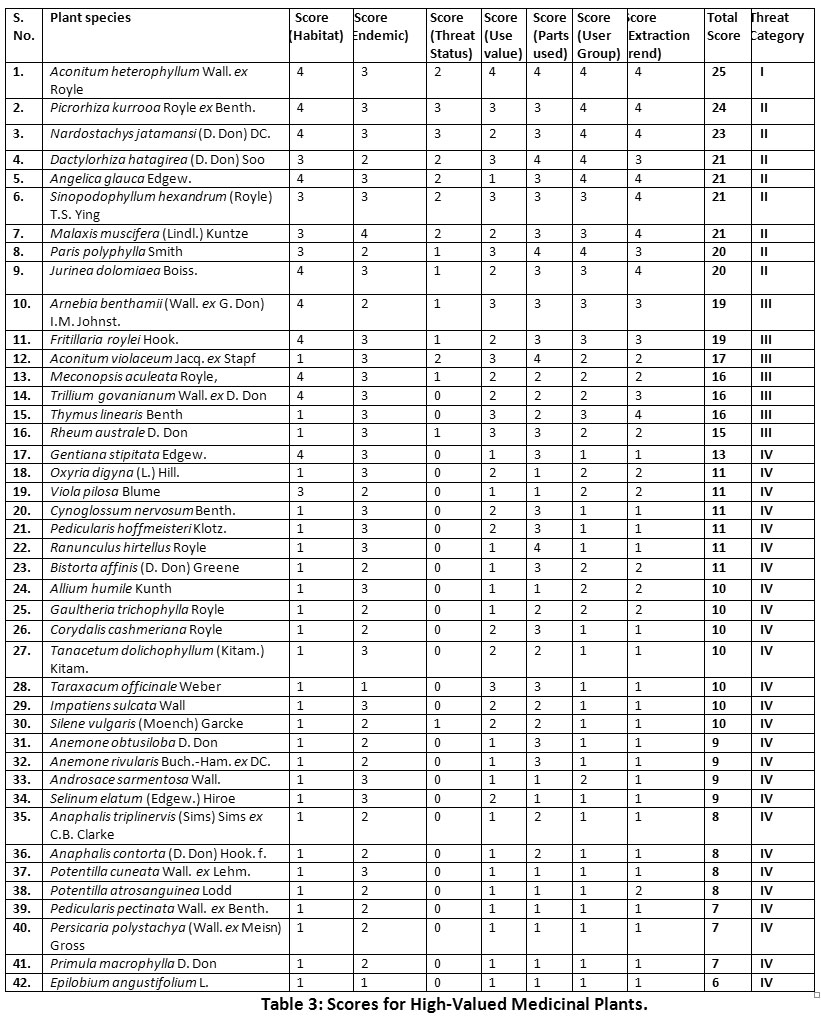

To get the final score, a complete list was created and the values of the relevant categories of each species were represented. The species were categorized into four threat categories as shown below (category I representing the most threatened and category IV the least threatened category) on the basis of the final score. For prioritization we used only three categories (Category I, II, & III) for developing effective conservation priorities.

Threat category I ≥28

Threat category II 20–24

Threat category III 15–19

Threat category IV <15

Results

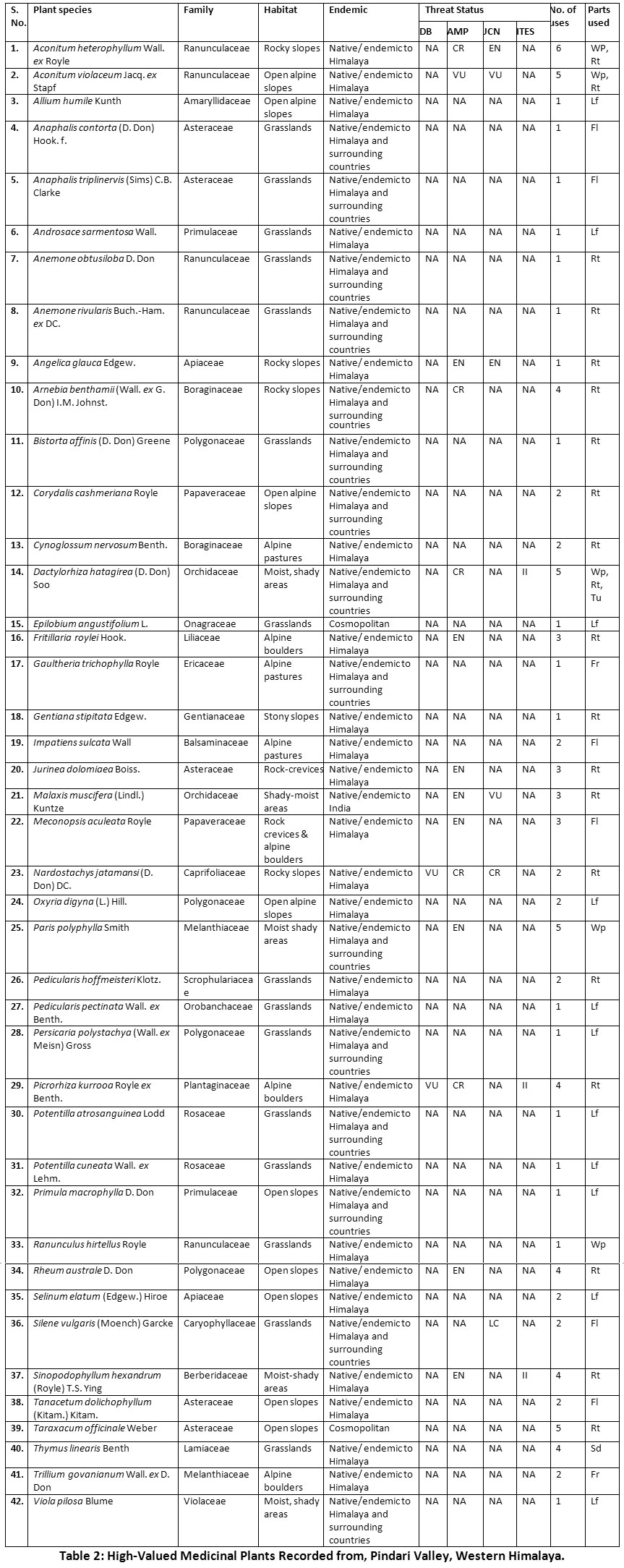

In the present study 42 species of High-value Medicinal Plants (HMPs) were documented on the basis of survey, ethnobotanical utilization and trade / market value (Table 2, Figure 2). Identified HMPs belong to 37 genera and 24 families. Asteraceae and Ranunculaceae are represented by 05 species each; Polygonaceae by 04 species; Apiaceae, Boraginaceae, Rosaceae, Primulaceae, Orchidaceae, Papaveraceae, Melanthiaceae by 02 species each; whereas single species represented Amaryllidaceae, Balsaminaceae, Berberidaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Ericaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Gentianaceae, Lamiaceae, Liliaceae, Violaceae, Plantaginaceae, Onagraceae and Orobanchaceae (Table 2).

Trade Value and Harvesting of THMPs

Sixteen species of THMPs are traded actively in the study area and Aconitum heterophyllum was recorded to be the highest with a cost up to Rs. 5000 per Kg. Picrorhiza kurrooa was the second highest traded species in the study area with a cost of about Rs. 4500 per Kg. Similarly, both Dactylorhiza hatagirea and Paris polyphylla were traded at the cost of approximately Rs 3600 per Kg. Few important species like, Angelica glauca fetched about Rs 2500-3000 per Kg and Trillium govanianum was sold at a price about Rs 2200 per Kg.

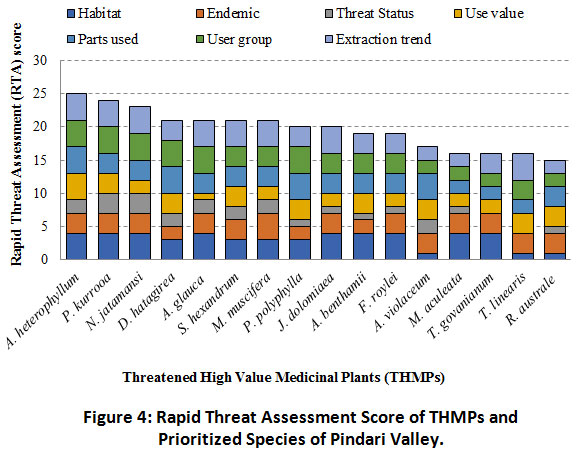

Rapid Threat Assessment

As per the Rapid Threat Assessment Score system opted in the study, the maximum aggregate score recorded for Aconitum heterophyllum (25) clearly indicate the highest threat categorization because of high extraction pressure, maximum number of uses and whole plant being used to treat various diseases and ailments in the study area. This was followed by Picrorhiza kurrooa with score 24, Nardostachys jatamansi with score of 23 and the four species Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Angelica glauca, Sinopodophyllum hexandrum, Malaxis muscifera the score of 21 each. Epilobium angustifolium scored the minimum (06) and can be considered as least threatened plant due to facing minimum extraction pressure and used to treat few diseases among the medicinal plants of Pindari Valley (Table 3). Out of the total recorded HMPs, 16 plant species were categorized under different threat categories of CAMP; 06 species are under IUCN; 03 species (P. kurrooa, D. hatagirea, S. hexandrum) are in the CITES (Appendix II) and 02 species (P. kurrooa and N. jatamansi) are in RDB (Table 2). Moreover, among the HMPs one species i.e., Aconitum heterophyllum was placed under the threat category I, whereas 08 species fell into threat category II, 07 species listed under threat category III and remaining 26 species were placed under least threat category IV (Table 3).

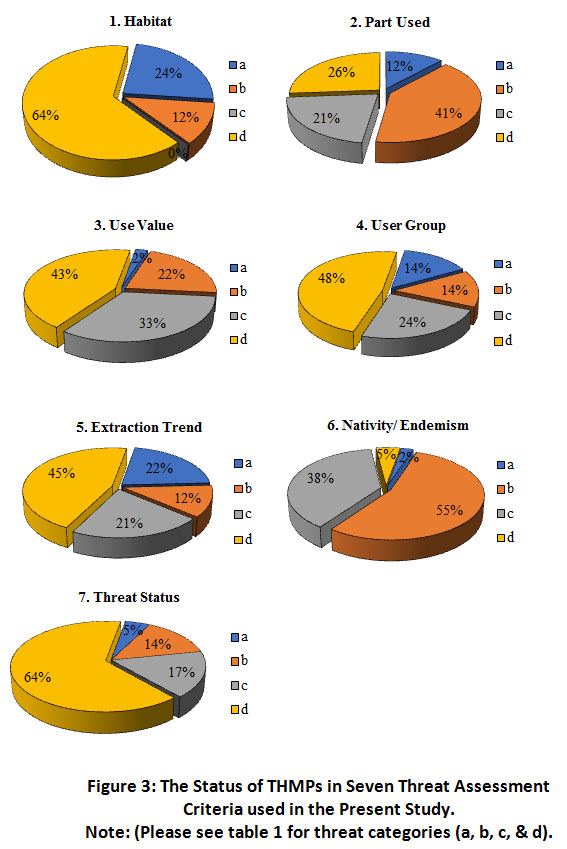

The threat assessment reported that 64% of the HMPs of Pindari Valley grow in grasslands/ alpine pastures, open/alpine slopes while 55% HMPs are native/endemic to Himalaya (Figure 3). In present study area, 48% of these HMPs are harvested by local people (Figure 3). For the preparation of medicines, different parts of HMPs are used (i.e., roots, rhizomes, inflorescences, leaves, bulbs, fruits and tubers) (Table 2). It is obvious that 40% plants utilized the underground portions (e.g., roots, rhizomes, tubers) may harm the life cycle. Further, 12% plant used as whole plants (in combination of both above and below ground portions) for different medicinal purposes, also affects the life of plant. The remaining 48% plants exploited for leaves, seeds, flower, etc. and can be considered sustainable. Around 64% plants are categorized in Least Concern category, but 5% plants have considered in Critically Endangered category (Figure 3).

Prioritisation of THMPs

Based on seven selected categories of Rapid Threat Assessment (RTA), such as habitat, plant used, use value, user group, extraction trend, nativity/endemism, threat status, a total of 16 plant species were identified and placed in three categories on the basis of their cumulative score (Figure 4).

Different parts of HMPs (i.e., roots, rhizomes, inflorescences, leaves, flowers, fruits, and tubers) are used for the preparation of medicines (Table 2). It is obvious that 40% plants utilized the underground portions (e.g., Aconitum heterophyllum fell under the most threatened category i.e., I. The species under category II of threat having higher scores were P. kurrooa, N. jatamansi, D. hatagirea, A. glauca, S. hexandrum, M. muscifera, P. polyphylla and J. dolomiaea. The species under threat category III were A. benthami, F. roylei, A. violaceum, M. aculeata, T. govanianum, T. linearis and R. australe.

|

Table 2: High-Valued Medicinal Plants Recorded from, Pindari Valley, Western Himalaya. Click here to view Table |

Abbreviations

Threat Status

CR= Critically Endangered; EN= Endangered; LC= Least Concern; VU= Vulnerable; NT= Near Threatened; NA= Not Evaluated; CAMP= Conservation Assessment and Management Plan; CITES= Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species; IUCN= International Union for Conservation of Nature; RDB= Red Data Book.

Plant Parts Used

Wp= Whole plant; Rt= Root, Lf= leaf; Fl= Flower; Fr= Fruit; Sd= Seed; Tu= Tuber.

|

Table 3: Scores for High-Valued Medicinal Plants. Click here to view Table |

|

Figure 2: Medicinal Plants of Pindari Valley. Click here to view Figure |

|

Figure 3: The Status of THMPs in Seven Threat Assessment Criteria used in the Present Study. Click here to view Figure |

|

Figure 4: Rapid Threat Assessment Score of THMPs and Prioritized Species of Pindari Valley. Click here to view Figure |

Discussion

This study revealed extensive information on the high use value of medicinal plants for the first time coupled with information on the level of threat, available conservation initiatives and prioritization based on importance of THMPs in the Pindari valley. Further, it exposes the therapeutic potential of 42 plant species having high potentials to cure different diseases. Among these enumerated plants, 54% (23 plants) were collected as whole plants or their underground parts extracted from the wild for use in herbal medicines and possess immense threat to natural vegetation.28,37 Nine of these species, viz. Aconitum heterophyllum, Arnebia benthamii, Angelica glauca, Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Fritillaria roylei, Meconopsis aculeata, Picrorhiza kurrooa, Sinopodophyllum hexandrum, and Thymus linearis have been already prioritized for conservation in the Indian Himalayan State of Uttarakhand22,28, and two species namely, Aconitum violaceum and Angelica glauca were categorized in IUCN categories. It is noticeable that 55% of the total prioritized species are native/ endemic to Himalaya and 2% species are native/ endemic to India. Due to the limited information on these endemic and threatened plants, the conservationists put more attention to authentic documentation, assessment and sustainable utilization towards conservation.38

The continuous increasing demand for these species in the pharmaceutical industries has been known from other regions of Himalaya and resulted depletion of wild resources.3,28 If the same situation like overexploitation proceeds, many species may reduce and eventually disappear from, their natural habitats. This especially applies to medicinal plants found in alpine Himalaya with multiple uses.39,40 Some very prominent medicinal plants in this region namely, Aconitum heterophyllum, Angelica glauca, Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Malaxis muscifera, Paris polyphylla and Picrorhiza kurrooa are already declining in population38 in mountain regions.1,16,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48

As per the present threat categorization, Aconitum heterophyllum is the most threatened species which is falling under threat category I. It is one of the most preferred species of the region, possess high medicinal use39,45 as well as trade value.49 Thus, the harvesting pressure is predominant threat factors for the species of category I. Further, the species under threat category II having higher scores were Picrorhiza kurrooa, Nardostachys jatamansi, Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Angelica glauca, and Sinopodophyllum hexandrum. All these species are preferred not only by residents of the Pindari Valley but also in other parts of Himalayas.24,25 Although some of these species are prohibited for collection, besides of this local people are totally dependent on these medicinal plants due to lack of the healthcare facility in the higher altitude region. All these five species under category II are extracted for their underground parts and are sometimes harvested without leaving any remains of whole plant due to unavailability of scientific knowledge, which prevents further regeneration.21 Hence, the species of category II mainly suffer from unscientific harvesting for frequently utilization by locals. In third category (category III) recorded by Arnebia benthamii, Fritillaria roylei, Aconitum violaceum, Meconopsis aculeata, Trillium govanianum, Thymus linearis and Rheum australe are identified as a least threatened species in the study area, in view of less demand in market as well as local level.

The results of this study could direct the local government and stakeholders in determining which species should be targeted at conservation. Nearly two-thirds of the existing priority species in this part of the world have not been evaluated in compliance with IUCN guidelines and therefore deserve urgent conservation assessment.50,51,52 Further, awareness on medicinal plants and conservation education to the local people needs to be provided for better understanding and sustainable utilization of these high-value medicinal plants.

Conclusion

The study revealed a total of 42 high-value medicinal plant species based on rapid threat assessment. Outcomes of the study suggested: (i) Aconitum heterophyllum with the highest score indicates that this species confronts the highest degree of threat among all the species. (ii) the study concluded that the demand of species, like Aconitum heterophyllum, Angelica glauca, Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Nardostachys jatamansi, Sinopodophyllum hexandrum and Paris polyphylla were high for various therapeutic purpose as well as trade value and needs major prioritization and conservation attention. (iii) providing awareness is an important tool for conservation as proper awareness among the local people is highly required. The threatened species can be promoted through cultivation in local village area for house-hold utilization may also reduce some pressure from wild. Further, the advance scientific techniques by using biotechnology can also be substituted for mass propagation and plantation in natural habitat for conservation. This study is an initial attempt to identify the endangered plant species, as also to draw the attention of conservation biologists, policy makers and researchers to implement conservation measures for these highly valuable plants

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Head, Botany Department, S. S. J. Campus, Kumaun University, Almora for providing necessary facilities and all informers of the study area, especially traditional Vaidyas and experienced persons, for revealing valuable information.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

References

- Rawat B., Chandra Sekar K., Gairola S. Ethnomedicinal plants of Sunderdhunga valley, Western Himalaya, India-traditional use, current status and future scenario. Indian For. 2013; 139(1): 61-68.

- Ved D. K., Mudappa A., Shankar D. Regulating export of endangered medicinal species-need for scientific rigour. Curr Sci. 1998; 75: 341-344.

- Dhar U., Rawal R. S., Upreti J. Setting priorities for conservation of medicinal plants - a case study in the Indian Himalaya. Biol. Conserv. 2000; 95(1): 57-65.

CrossRef - Wake D. B., Vredenburg V. T. Are we in the midst of the sixth mass extinction? A view from the world of amphibians. PNAS. 2008; 105: 11466-11473. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0801921105.

CrossRef - Cardinale B. J., Duffy J. E., Gonzalez A., Hooper D. U., Perrings C., Venail P., Narwani A., Mace G. M., Tilman D., Wardle D. A., Kinzig A. P., Daily G. C., Loreau M., Grace J., Larigauderie B., Srivastava A., Naeem D. S. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature.2012; 486: 59-67. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11148.

CrossRef - Parr M. J., Bennun L., Boucher T., Brooks T., Chutas C.A., Dinerstein E., Drummond G.M., Eken G., Fenwick G., Foster M., Martínez-Gómez J. E., Mittermeier R., Molur S. Why we should aim for zero extinction. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009; 24(4): 181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.01.001.

CrossRef - Wilson H. B., Joseph L. N., Moore A. L., Possingham H. P. When should we save the most endangered species? Ecol Lett. 2011; 14(9): 886-890. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01652.x.

CrossRef - Gauthier P., Debussche M.,Thompson J. D. Regional priority setting for rare species based on a method combining three criteria. Biol. Conser. 2010; 143(6): 1501-1509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.03.032.

CrossRef - Pimm S. L., Jenkins C. N., Abell R., Brooks T. M., Gittleman J. L., Joppa L. N., Raven P. H., Roberts C. M., Sexton J. O. The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection. Science. 2014; 344(6187): 1246752. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1246752.

CrossRef - Mehta P., Bisht K., Chandra Sekar. K. Diversity of threatened medicinal plants of Indian Himalayan Region. Plant Biosyst. 2020; 1-12. https://doi: 10.1080/11263504.2020.1837278.

CrossRef - Brehm J. M., Maxted N., Martins-Loucao M. A., Ford-Lloyd B.V. New approaches for establishing conservation priorities for socio-economically important plant species. Biodivers Conserv. 2010; 19: 2715-2740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-010-9871-4.

CrossRef - Sapir Y., Shmida A., Fragman O. Constructing Red Numbers for setting conservation priorities of endangered plant species: Israeli flora as a test case. J. Nat. Conserv. 2003; 11(2): 91-107. https://doi.org/10.1078/1617-1381-00041.

CrossRef - Kala C. P., Farooquee N. A., Dhar U. Prioritization of medicinal plants on the basis of available knowledge, existing practices and use value status in Uttaranchal, India. Biol. Conserv. 2004; 13(2): 453-469. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BIOC.0000006511.67354.7f.

CrossRef - Bisht M., Chandra Sekar, K., Arya D. Diversity, Utilization pattern, Threat status and Conservation of Medicinal Plants in Great Himalayan National Park, Himachal Pradesh, Western Himalaya. Asia Pac. J. Re. 2019; 36-48.

- Kumar R., Arya D., Chandra Sekar, K. Diversity, utilization patterns and conservation of ethnomedicinal plants in Pindari Valley, Uttarakhand Himalaya. Asia Pac. J. Re. 2020; 1-11.

- Kala C. P., Rawat G. S., Uniyal V. K. Ecology and conservation of the Valley of Flowers National Park, Garhwal Himalaya, WII, Dehradun.1998.

- Kala C. P. Status and conservation of rare and endangered medicinal plants in the Indian trans-Himalaya. Biol. Conserv. 2000; 93(3): 371-379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(99)00128-7.

CrossRef - Gaur R. D. Flora of the District Garhwal North West Himalaya with ethnobotanical notes. Srinagar (Garhwal) India: Transmedia Publication. 1999.

- Maikhuri R. K., Nautiyal S., Rao K. S., Saxena K. G. Medicinal plants cultivation and biosphere reserve management: a case study from Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, Himalaya. Curr. Sci. 1998; 74(2): 157-163.

- Chandra Sekar, K., Srivastava S. K. Flora of the Pin valley National Park, Himachal Pradesh, India. Botanical Survey of India, Kolkata. 2009.

- Chandra Sekar, K., Rawat B. Diversity, utilization and conservation of ethnomedicinal plants in Devikund - A high altitude, sacred wetland of Indian Himalaya. Medicinal plants- International Journal of Phytomedicines and Related Industries. 2011; 3: 105-112. https://doi.org/10.5958/J.0975-4261.3.2.017.

CrossRef - Negi V., Kewlani P., Pathak R., Bhatt D., Bhatt I. D., Rawal R. S., Sundriyal R. C., Nandi S. K. Criteria and indicators for promoting cultivation and conservation of medicinal and aromatic plants in Western Himalaya, India. Ecol. Indic. 2018; 93: 434-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.03.032.

CrossRef - Bisht M., Chandra Sekar. K., Kant R., Ambrish K., Singh P., Arya D. Floristic diversity in Valley of Flowers National Park, Indian Himalayas. Phytotaxa, 2018; 379(1): 001-026. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.379.1.1.

CrossRef - Joshi B., Chandra Sekar. K. Ethno-medicinal notes of Hat-Kalika watershed in West Himalaya. J. Mountain Res.2018; 13: 9-14.

- Joshi B.C., Rawal R.S., Chandra Sekar. K., Pandey A. Quantitative ethnobotanical assessment of woody species in a representative watershed of west Himalaya, India. Energy, Ecology and Environment. 2019; 4: 56-64.

CrossRef - Cunningham A. B. People, park and plant use: recommendations for multiple-use zones and development alternatives around Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda. (4). Paris, UNESCO. 1996.

- Shrestha N., Shrestha K. K. Vulnerability assessment of high-valued medicinal plants in Langtang National Park, Central Nepal. Biodiversity. 2012; 13(1): 24-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386. 2012.666715.

CrossRef - Pandey A., Chandra Sekar, K., Joshi B., Rawal, R. S. Threat assessment of high value medicinal plants of cold desert areas in Johar valley, Kailash Sacred Landscape, India. Plant Biosystems. 2018; 153(1): 39-47. https://doi.org/10.1080/11263504.2018.1448010.

CrossRef - Tali B. A., Khuroo A. A., Nawchoo I. A., Ganie A. H. Prioritizing Conservation of Medicinal Flora in the Himalayan Biodiversity Hotspot: An Integrated Ecological and Socioeconomic Approach. Environ. Conserv. 2019; 147-154. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892918000425.

CrossRef - Samant S. S., Pant S., Singh M., Lal M., Singh A., Sharma A., Bhandari S. Medicinal plants in Himachal Pradesh, North Western Himalaya, India. Int J Biodiv Sci Manag. 2007; 3(4): 234-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/17451590709618177.

CrossRef - Hooker J. D. The Flora of British India. London-reprinted in 1982 by Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, Dehra Dun, India, vols. I-VII. 1875.

CrossRef - Pusalkar P. K., Singh D. K. Flora of Gangotri National Park, Western Himalaya, India. Kolkata: Botanical Survey of India. 2012.

- CAMP, Conservation Assessment & Management Prioritization of elected medicinal plants of Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh & Uttaranchal. In: Ved DK, Kinhal GA, Ravikumar K, Prabhakaran V, Ghate U, Shankar RV, Indresha JH. (Eds.) FRlHT, Bangalore, India. 2003.

- CITES. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. 2011. http://www.cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php.

- IUCN. The IUCN Red list of threatened species, version 2016.4. IUCN Red list Unit, Cambridge U.K. 2018. Available from: http://www.iucnredlist.org/(accessed 03 August 2018).

- Nayar M. P., Sastry A. R. K. Red Data Book of Indian Plants, Vol. III. Calcutta: Botanical Survey of India. 1987, 1988 & 1990.

- Bisht V. K., Negi J. S., Bhandari A. K. Check on extinction of medicinal herbs in Uttarakhand: no need to uproot. Natl Acad Sci Lett. 2016; 39: 233-235.

CrossRef - Khan S. M., Page S., Ahmad, H., Harper D. Identifying plant species and communities across environmental gradients in the Western Himalayas: method development and conservation use. Eco Infor. 2013; 14: 99-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2012.11.010.

CrossRef - Samant S. S., Dhar U., Palni L. M. S. Medicinal Plants of Indian Himalaya. Himavikas Publication-13, GBPIHED Kosi, Almora, India. 1998.

- Samant S. S., Pal M. Diversity and conservation status of medicinal plants in Uttaranchal State. Indian For. 2003; 129(9): 1090-1108.

- Singh G. Diversity of vascular plants in some parts of Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary (Western Himalaya) [PhD thesis].2008. Uttarakhand: Kumaun University Nainital.

- Nautiyal B. P., Prakash V., Bahuguna R., Maithani U. C., Rajashekran C., Bisht H.,Nautiyal M. C. Population study for monitoring the status of rarity of three aconite species in Garhwal Himalaya. Trop. Eco. 2002; 43(2): 297-303.

- Nautiyal B. P., Chauhan R. C., Prakash V., Purohit H., Nautiyal M. C. Population studies for the evaluation of germplasm and threat status of the alpine medicinal herb Nardostachys jatamansi. Plant Genet Resour Newsl. 2003; 136: 34-39.

- Uniyal S. K., Awasthi A., Rawat G. S. Current status and distribution of commercially exploited medicinal and aromatic plants in upper Gori Valley, Kumaon Himalaya. Curr. Sci. 2002; 82(1): 1246-1252.

- Kala C. P. Indigenous uses, population density, and conservation of threatened medicinal plants in protected areas of the Indian Himalayas. Biol. Conserv. 2005; 19(2): 368-378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00602.x.

CrossRef - Singh K. N., Gopichand A. K., Lal B. Species diversity and population status of threatened plants in different landscape elements of the Rohtang pass, Western Himalaya. J Mt Sci. 2007; 5(1): 73-83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-008-0073-4.

CrossRef - Chauhan R. S., Nautiyal M. C., Prasad P., Purohit H. Ecological features of an endangered medicinal orchid- Malaxis muscifera (Lindley) Kuntze in the Western Himalaya. Mt Res Dev. 2008; 9(6): 8-12.

- Anon, 2010. CITES.web:http://www.cites.org/eng/resources/pub/checklist08/Checklist. pdf.

- Kuniyal C. P., Kuniyal P. C., Butola J. S., Sundriyal R. C. Trends in the marketing of some important medicinal plants in Uttarakhand, India. Int J Biodiv Sci Ecosyst Serv Manag. 2013; 9(4): 324-329. https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732. 2013.819531.

CrossRef - Tali B. A., Ganie A. H., Nawchoo I. A., Wani A. A., Reshi Z. A. Assessment of threat status of selected endemic medicinal plants using IUCN regional guidelines: a case study from Kashmir Himalaya. J. Nat. Conserv. 2015; 23: 80-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2014.06.004.

CrossRef - Mehta P., Chandra Sekar. K., Bhatt D., Tewari A., Bisht K., Upadhyay S., Negi V.S., Soragi B. Conservation and prioritization of threatened plants in Indian Himalayan Region. Biodivers Conserv. 2020; 29(6): 1723-1745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-01959-x.

CrossRef - Negi V. S., Giri, L., Chandra Sekar. K. Floristic diversity, community composition and structure in Nanda Devi National Park after prohibition of human activities, Western Himalaya, India. Curr. Sci. 2018; 115 (6): 1056-1064.

CrossRef