Consumer’s Intention to Purchase Green Brands: the Roles of Environmental Concern, Environmental Knowledge and Self Expressive Benefits

Anees Ahmad1 * and K. S. Thyagaraj1

1

Department of Management Studies,

Indian School of Mines,

Dhanbad,

826004

Jharkahnd

India

Corresponding author Email: anees.candytuft@gmail.com

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.10.3.18

Companies are striving to minimize environmental impact through sustainable business practices. Consumers have become more aware of environmental issues and many companies have recognized the relevance of green marketing in gaining competitive advantage. As a part of green marketing strategy, companies are developing green brands. This paper focuses on the effect of consumer’s concern for environment, environmental knowledge and self expressive benefits on attitude and intention to purchase green brand. Data were collected from 270 Indian consumers. The results of this research show that environmental concern, environmental knowledge and self expressive benefits would positively influence attitude which in turn positively influences intention to purchase green brands. The influence of consumer’s knowledge of the environment on purchase intention was found to be non-significant. Hence, investing resource to promote environmental concern, to impart environmental knowledge and to communicate self expressive benefits will be helpful in increasing purchase intentions of green brands.

Copy the following to cite this article:

Ahmad A, Thyagaraj K. S. Consumer’s Intention to Purchase Green Brands: the Roles of Environmental Concern, Environmental Knowledge and Self Expressive Benefits. Curr World Environ 2015;10(3) DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.10.3.18

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Ahmad A, Thyagaraj K. S. Consumer’s Intention to Purchase Green Brands: the Roles of Environmental Concern, Environmental Knowledge and Self Expressive Benefits. Available from: http://www.cwejournal.org/?p=13142

Download article (pdf)

Citation Manager

Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Publishing History

| Received: | 2015-10-07 |

|---|---|

| Accepted: | 2015-11-26 |

Introduction

Environmental issues are increasingly gaining importance among societies worldwide.1 In the process of developing new products, climate change emerges as an issue of strategic importance because companies are considering climate change related risks and opportunities in product planning. Consumer’s environmental knowledge and concern and environmental regulations such as Kyoto Protocol and Montreal Convention are deeply influencing world business.2 In this context, many companies are transforming their entire business process to be eco friendly and are embracing a green marketing strategy to position their products. This shows a paradigm shift in business thinking towards the environment and the society.3 Integrating sustainability into business practices yields several benefits like product differentiation, resource utilization, enhanced competitive advantage and corporate image.4,5,6,7 Green product and green process innovation drives firm’s competitive advantage.2 Sustainability and continuity of business highly depends on the manner in which firm deals with environmental problems.8 Moreover, environmental investments unfurl plenty of profitable business opportunities.9 Hence, going green results in many benefits such as bottom line cost savings, brand recognition and competitive advantage to a company.

Environmental concern and sustainability has resulted in a proliferation of green brands across product categories.10 Previous research indicates a positive relationship between environmental knowledge and consumer behavior.11 Several brand positioning strategies are encompassing green initiatives like environment friendly, organic and energy efficient.12 Experiential benefits derived by the green brand consumers, influence their need satisfaction in terms of environmental care and contribution to the social well-being.13 Research suggests that consumer’s inherent concern about society and environment drives conservation behavior.14 In comparison to the general population green consumers are more environmentally concerned.15,16 Moreover, consumers also expect self expressive benefits from consumption of environmentally friendly products.17,18 Being a psychological motive, self expression enhances the possibility of green brand purchase. Previous research also suggests that attitude toward eco-friendly products are an important variable in understanding the consumer’s perception of green brand.19,20,21 Therefore, this study investigates the impact of consumer’s concern for environment, environmental knowledge and perceived self expressive benefits on attitude and intention to buy green brands.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Environmental Concern

Environmental concern indicates ‘the degree to which people are aware of problems regarding the environment and support efforts to solve them or indicate the willingness to contribute personally to their solution’.22 As suggested by the general environmental attitudes, the principal determinants of eco-friendly consumption are values and environmental concern.23,24 Readiness to change the behavior backed by degree of emotionality and environmental knowledge defines environmental concern.25 Environmental concern has been represented as the evaluation of individual behavior or collective behavior with repercussions for the environment.26 Environmental concern also indicates a strong attitude towards environmental preservation.27 Environmental research is fundamentally based on individual’s concern for the environment which directly affects pro environmental behavior. Consumer’s intrinsic concern about the society and environment reflects in conservation behavior.28 Environmental concern is a major factor in consumer decision making.29,30 Various other studies emphasize that environmental concern influences purchase behavior of eco-friendly products.23,31 High environmental concern in consumers induces support for green products and consumers readily choose them while purchasing.32 A number of empirical studies indicate strong relationship between environmental concern and purchase intention/ pro-environmental buying behavior. Environmental concern positively influences the green purchase intention and behavior.20,31,33,34,35,36 In the study of Choi and Kim,34 consumers with higher concern for the environment were found more willing to purchase green products in comparison to the consumers with low concern for the environment. Though most of the studies show a direct impact of environmental concern on consumer’s green purchase intentions, yet in the studies of Han et al.19 and Hartmann and Apaolaza,20 attitude toward green products act as a mediator between environmental concern and green purchase intention.

Environmental Knowledge

Environmental knowledge indicates how much awareness people have about the environment with regard to collective responsibilities necessary for sustainable development and key relationships leading to environmental aspects or impacts.37 Research suggests a positive relationship between environmental knowledge and consumer behavior.11,38 The level of consumer’ knowledge about environmental issues determines their purchase behavior and factual knowledge is prerequisite in attitude formation39. According to Arcury40, environmental knowledge changes environmental attitude and both environmental knowledge and environmental attitude affect the behavior of consumer. Individual’s knowledge of environmental and green issues is generally associated with purchase behavior of consumers.41,42 Peattie43 postulates that environmental knowledge has often being considered as principal motivating factor of green consumer behavior. According to Mostafa44 and Rokicka,45 consumer’s awareness about environment has a positive impact on the willingness to purchase green products which in turn results into pro-environmental behavior. In the study of Stern,46 the individuals who had knowledge about the specific problem and how to act in order to deal it with in a better way were found more actively engaged in comparison to the individuals who were ignorant. Chan and Lau47 considered ecological knowledge as the predictor of green buying intention and their research result shows that people with higher ecological knowledge in China had a strong willingness to buy green products. Moreover, in a number of studies, there is a significant relationship between environmental knowledge and attitude toward green product which in turn influences the consumers’ green purchase intentions.48,49,50,51

Self-Expressive Benefits

Apart from functional and emotional benefits consumers also derive self expressive benefits.52 The concept of self expressive benefits is based on signaling theory which states that consumer is involved in consumption of environmentally friendly products because they have social visibility.17 Signaling refers to the process of implicitly expressing one’s information of preferences and personal traits to others. According to Glazer and Konrad,53 the higher chances of signaling make the individual to consume in a manner that benefits society. The association of high signaling products with pro-environmental behaviors yields higher self expressive benefits54 and this notion is well endorsed by research on symbolic consumption.55 According to Solomon,56 the product an individual consumes defines consumer’s social role and consumer is involved in eco-friendly consumption with a view to exhibit pro-environmental attitude. Moreover, consumers may also be involved in eco-friendly consumption in order to signal their altruistic behavior. Van et al.57 argues that conspicuous altruism helps in attaining reputation because individuals exhibit their willingness to engage in social welfare. The motives of status and reputation encourage consumer to purchase green products.58 Hence, self expressive benefits are positively linked with pro environmental consumption and behavior.

Based upon the literature, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Environmental concern significantly influences attitude toward green brand.

H2: Environmental concern significantly influences intention to purchase green brand.

H3: Environmental knowledge significantly influences attitude toward green brand.

H4: Environmental knowledge significantly influences intention to purchase green brand.

H5: Self expressive benefits significantly influence attitude toward green brand.

H6: Self expressive benefits significantly influence intention to purchase green brand.

H7: Attitude toward green brand significantly influences intention to purchase green brand.

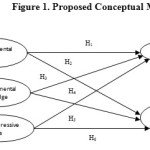

Figure 1: shows the conceptual model which represents our corpus of seven research hypotheses.

|

|

Methods

Data Collection

Questionnaire survey was used in this study to verify the hypotheses and conceptual framework. Primary data were collected from a convenience sample of 270 Indian respondents who had the purchase experience of electronic products. ‘Consumer electronics’ is one of the industries that have a strong commitment to sustainable practices in order to minimize environmental impact. This industry has taken a range of green initiatives in the areas of green manufacturing, design and energy efficiency, and clean delivery systems.

Table 1: Presents the demographic composition of the respondents.

|

Age |

20-25 5(1.8%) |

26-30 86 (31.9%) |

31-35 112 (41.5%) |

36 and above 67 (24.8%) |

|

Gender |

Male 148 (54.8%) |

Female 122 (45.2%) |

||

|

Education |

Under Graduate 1(4%) |

Graduate 84 (31.1%) |

Post Graduate 166 (61.5) |

Doctoral Degree 19 (7%) |

|

Occupation |

Pvt. Services 188 (69.6 %) |

Business 38 (14.1 %) |

Govt. Job 21 (7.8 %) |

Self Employed 23 (8.5 %) |

Measurements

The respondent evaluated the constructs of environmental concern, environmental knowledge, self expressive benefits, attitude and purchase intention on the Likert scale with five points (1= strongly disagree, 5= strongly agree). Table 2 summarizes the measures and sources of constructs used in the study.

Table 2: Model Constructs, Survey Measures and Scale Source

|

Construct |

Survey measures |

Scale adopted from |

|

Environmental Concern |

EC1: Environment is severely abused by humans EC2: Uncontrolled expansion of the industrialized society must be checked EC3: We must maintain the balance of nature for our survival EC4: The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset. |

Mostafa.44 Chen and Tung59 |

|

Environmental Knowledge |

EK1: I know more about recycling than the average person. EK2: I understand the environmental phrases and symbols on product package. EK3: I am very knowledgeable about environmental issues |

Mostafa60 |

|

Self Expressive Benefits |

SEB1: With brand X, I can express my environmental concern SEB2: With brand X, I can demonstrate to myself and my friends that I care about environmental conservation SEB3: With brand X, my friends perceive me to be concerned about the environment |

Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez20,61 |

|

Attitude |

ATT1: For me, purchasing a green brand is: Good ATT2: For me, purchasing a green brand is: Desirable ATT3: For me, purchasing a green brand is: Wise ATT4: For me, purchasing a green brand is: Enjoyable |

Kim and Han62 |

|

Purchase Intention |

PI1: I will prefer to purchase a green brand over a non- green brand PI2: I am willing to purchase a green brand for ecological reasons PI3: I will make an effort to purchase a green brand |

Kim et al.63 |

Results

The researchers applied the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to verify the conceptual framework and hypotheses. Empirical results were obtained by applying SPSS version 20 and AMOS version 21. Two levels of analysis namely measurement model and structural model and their results are as follows:

Measurement Model: Reliability and Validity

The measurement model provides the quantitative measures regarding the reliability and validity of constructs used in the study. For assessing convergent validity of the construct, composite reliability, Factor loading, Average variance extracted (AVE) and Cronbach’s alpha were used.

Table 3: Measurement model: Reliability and Validity

|

Constructs |

Items |

Standardized Factor Loading |

Squared Multiple Correlation (SMC) |

Cronbach’s α |

Composite Reliability |

A.V.E. |

|

Environmental Concern |

EC1 EC2 EC3 EC4 |

0.85 0.82 0.81 0.84 |

0.72 0.67 0.65 0.70 |

0.89 |

0.94 |

0.68 |

|

Environmental Knowledge |

EK1 EK2 EK3 |

0.77 0.76 0.92 |

0.59 0.57 0.85 |

0.85 |

0.82 |

0.67 |

|

Self Expressive Benefits |

SEB1 SEB2 SEB3 |

0.75 0.68 0.71 |

0.56 0.46 0.50 |

0.75 |

0.71 |

0.51 |

|

Attitude |

ATT1 ATT2 ATT3 ATT4 |

0.71 0.73 0.67 0.68 |

0.51 0.53 0.44 0.46 |

0.81 |

0.70 |

0.49 |

|

Purchase Intention |

PI1 PI2 PI3 |

0.78 0.63 0.79 |

0.61 0.39 0.62 |

0.81 |

0.73 |

0.54 |

The reliability and validity of the constructs was tested subject to the suggestions given by Fornel and Lacker.64 All the constructs showed a standardized factor loading above 0.5 (ranging from 0.63 to 0.92) thus indicating good convergent validity among all the latent variables. Cronbach’s α was used to measure the internal consistency among items which ranged from 0.75 to 0.89 indicating a good consistency.65 All values of composite reliability surpass the minimum threshold of 0.60.66 The AVE ranges from 0.49 to .68, meeting the minimum acceptable limit of 0.5. Moreover, Square Multiple Correlation (SMC) was also used to ensure discriminant validity of each item. SMC value of each item was found less than its standardized factor loading64 and the value was also above the minimum criterion of 0.3.66 Table 3 lists all of these values.

Finally discriminant validity among the constructs was also validated as the Average Variance Extracted was greater than the correlation of each construct.67 Table 4 summarizes the values of correlations and square root of Average Variance Extracted.

Table 4: Correlation among the constructs

|

Mean |

S.D. |

EC |

EK |

SEB |

ATT |

PI |

|

|

EC |

3.992 |

0.823 |

0.82 |

||||

|

EK |

3.954 |

0.958 |

0.431** |

0.81 |

|||

|

SEB |

3.874 |

0.857 |

0.542** |

0.460** |

0.71 |

||

|

ATT |

3.929 |

0.897 |

0.453** |

0.514** |

0.585** |

0.70 |

|

|

PI |

3.733 |

0.925 |

0.518** |

0.442** |

0.560** |

0.599** |

0.73 |

Note: Diagonals (Bold and Italics) represent the square root of average variance extracted while the other entries represent the correlation, mean and S.D. (standard deviation). **p<0.01

The results of the structural model

The goodness of fit statistics of the structural model was tested using measures of model fit namely: Goodness of Fit index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI) and Root Mean Square Approximation Method (RMSEA). Table 5 shows the summary of statistical results.

Table 5: Chi-square result and goodness of fit indices of the proposed model

|

Fit Indices |

Obtained Value |

Norm* |

|

χ2 |

263.210 |

N/A |

|

Scaled χ2/df |

2.437 |

>1 and <5 |

|

Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index(AGFI) |

0.901 0.849 |

>0.90 >0.8** |

|

Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) |

0.915 |

>0.90 |

|

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) |

0.933 |

>0.90 |

|

Incremental Fit Index (IFI) |

0.934 |

>0.90 |

|

Root Mean Square Approximation Method (RMSEA) |

0.07 |

<0.08 |

*Norm: Sources: Bagozzi and Yi66 ** Norm for AGFI: Chau and Hu68

On the basis of these measurements, the result of the study shows that our proposed model has a reasonable data fit (χ2= 263.210 (p=.000), χ2/df= 2.437, GFI=0.901, TLI=0.915, CFI=0.933, IFI=0.934, RMSEA= 0.07).

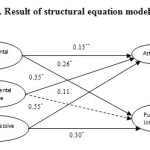

The finding shows that environmental concern (β= 0.15, p=0.011), environmental knowledge (β= 0.35, p=0.000) and self expressive benefits (β= 0.55, p=0.000) significantly influence attitude toward green brand. Hence, H1, H3 and H5 are supported. Further, environmental concern (β= 0.26, p=0.000) and self expressive benefits (β= 0.30, p=0.000) were found having significant influence on intention to purchase green brand which supports H2 and H6 but environmental knowledge has no significant influence on purchase intention (β= 0.11, p=0.115). Hence, H4 is not supported. Finally, Attitude toward the green brand has a positive significant influence on participant’s intention to purchase (β=0.39, p=0.000) which supports H7 (See Table 6 and Figure 2).

Table 6: Path analysis of structural model

|

Path |

Standardized Estimates |

t-statistics |

p-value |

Relationship |

|

EC → ATT |

0.15 |

2.539 |

0.011 |

Significant |

|

EC → PI |

0.26 |

4.249 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

EK → ATT |

0.35 |

5.324 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

EK → PI |

0.11 |

1.576 |

0.115 |

Not Significant |

|

SEB → ATT |

0.55 |

6.651 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

SEB → PI |

0.30 |

3.300 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

ATT → PI |

0.39 |

3.802 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

|

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand the effect of consumer’s environmental concern, environmental knowledge and perceived self expressive benefits on attitude and intention to purchase green brands. The results indicate that environmental concern among Indian consumers and self expressive benefits significantly influence their intention/willingness to buy the green brand. However, findings do not support the influence of environmental knowledge on purchase intention. Further, consumer’s environmental concern, environmental knowledge and self expressive benefits positively influence attitude towards green brand which in turn influences purchase intention positively. The findings of the study suggest that the more consumers are concerned for environment, the more likely they intend to purchase a green brand. Similarly, in case of self expressive benefits, the more consumers desire for status and reputation, the higher is their intention to purchase a green brand. Environmental knowledge though did not influence purchase intention directly but an increase in consumer’s environmental knowledge can result in positive attitude formation which results in increased intention to purchase a green brand. Self expressive benefits are also important mainly due to psychological benefits that a consumer derives while contributing to the environmental improvement.20

The results of the study exhibits direct implications for marketers of green brands. First, the marketers must promote concern for environmental protection. The development of high concern for environment will result in consumer’s increased preference for green brands. Second, the marketers should come up with programs to impart environmental knowledge to consumers. The increase in the level of environmental knowledge will form positive attitude for green brands and consequently the consumers will be more willing to purchase a green brand. Third, the marketers should design a marketing communication program that informs the consumers of self expressive benefits involved in purchase of green brands. In this context, advertisements aimed at fulfilling desires of status and reputation through conspicuous consumption of eco-friendly products can be very helpful.

While the present study serves as an addition to the existing knowledge, still the study has some limitations. First of all this study focuses on purchase experience of electronic products. Further research could consider other products and compare with this study. Second, this study takes into account the cross sectional data which cannot observe the dynamic changes in consumer’s environmental concern, knowledge and self expressive benefits. Future research could conduct a longitudinal study to observe any change over a period of time. Lastly, the participants of this study are Indian consumers. Future research could concentrate on consumers of other countries and compare with this study.

Refrences

- Chen, Y. S., The driver of green innovation and green image – green core competence. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(3): 531-543 (2008).

- Chen, Y. S., Lai, S. B. and Wen, C. T., The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan, Journal of Business Ethics, 67(4): 331-339 (2006).

- Berger, I.E., Cunningham, P. H. and Drumwright, M. E., Mainstreaming corporate social responsibility: developing markets for virtue. California Management Review, 49 (4):132-57 (2007).

- Shrivastava, P., Environmental technologies and competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 16 (3): 183-200 (1995).

- Miles, M.P. and Covin, J.G., Environmental marketing: a source of reputational, competitive, and financial advantage, Journal of Business Ethics, 23 (3): 299-311 (2000).

- Fraj-Andre’s, E., Martinez-Salinas, E. and Matute-Vallejo, J., A multidimensional approach to the influence of environmental marketing and orientation on the firm’s organizational performance, Journal of Business Ethics, 88 (2): 263-86 (2008).

- York, J., Pragmatic sustainability: Translating environmental ethics into competitive advantage, Journal of Business Ethics, 85 (1): 97-100 (2009).

- Baker, E.W. and Sinkula, M.J., Environmental marketing strategy and firm performance: effects on new product performance and market share, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33 (4): 461-75 (2005).

- Reinhardt, F., Market failure and the environmental policies of firms: economic rationales for ‘beyond compliance’ behavior, Journal of Industrial Ecology, 3 (1): 9-21 (1999).

- Wheeler, M., Sharp, A., and Nenycz-Thiel, M., The effect of ‘green’messages on brand purchase and brand rejection, Australasian Marketing Journal,21(2): 105-110 (2013).

- Park, C. W., Mothersbaugh, D. L., and Feick, L., Consumer knowledge assessment.Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1): 71-82 (1994).

- Parker, , Segev, S. and Pinto, J.,What it Means to Go Green: Consumer Perception of Green Brands and Dimensions of Greenness, Florida International University, North Miami, FL (2009).

- Rios, F., Martinez, T., Moreno, F. and Soriano, P., Improving attitudes toward brands with environmental associations: an experimental approach, The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23 (1):26-34 (2006).

- Bamberg S., How does environmental concern influence speciï¬c environmentally relat- ed behaviors? A new answer to an old question, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23(1): 21–32 (2003).

- Clark C.F., Kotchen M.J. and Moore M.R., Internal and external influences on proenvironmental behavior: participation in a green electricity program, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23(3):237–46 (2003).

- Hansla A., Gamble A., Juliusson A. and Gärling T., The relationships between awareness of consequences, environmental concern, and value orientations, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(1):1–9 (2008).

- Aaker J.L., The malleable self: the role of self-expression in persuasion, Journal of Marketing Research, 36(1):45–7 (1999).

- Aaker D.A., Building strong brands, Free Press, New York, (2002).

- Han, H., Hsu, L.T. and Lee, J.S. (2009), Empirical investigation of the roles of attitudes towards green behaviors, overall image, gender, and age in hotel customers' eco-friendly decision-making process, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28 (4): 519-528 (2009).

- Hartmann, P. and Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V., Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern, Journal of Business Research,65(9): 1254-1263 (2012).

- Mostafa, M. M., A hierarchical analysis of the green consciousness of the Egyptian consumer,Psychology and Marketing, 24(5), 445-473 (2007).

- Dunlap, R.E and Jones, R., Environmental Concern: Conceptual and Measurement Issues”. In Handbook of Environmental Sociology edited by Dunlap and Michelson. Greenwood press, London (2002).

- Balderjahn I., Personality variables and environmental attitudes as predictors of ecologically-responsible consumption patterns, Journal of Business Research, 17(1):51–6 (1988).

- Diamantopoulos, A., Schlegelmilch, B. B., Sinkovics, R. R. and Bohlen, G. M., Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation, Journal of Business Research, 56 (6): 465- 480 (2003).

- Maloney, M.P., Ward, M.P. and Braucht, G.N. (1975), Psychology in action: a revised scale for the measurement of ecological attitudes and knowledge. American Psychologies, 30: 787-790 (1975).

- Weigel, R.H., Environmental Attitudes and Prediction of Behavior, In N.R Feimer and E.S Geller, (Eds), Environmental Psychology: Directions and Perspectives, Preager, New York, 257-287 (1983).

- Crosby, L. A., Gill, J. D. and Taylor, J. R., Consumer/voter behavior in the passage of the Michigan container law.The Journal of Marketing, 45 (2):19-32 (1981).

- Fransson, N. and Gärling T., Environmental concern: conceptual deï¬nitions, measurement methods, and research findings, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 19(4): 369–82 (1999).

- Ottman, J.A., Green Marketing: Opportunity for Innovation. 2nd ed., NTC Business Books, Chicago, IL (1998).

- Zimmer, M. R., Stafford, T. F. and Stafford, M. R., Green issues: dimensions of environmental concern, Journal of Business Research, 30(1): 63-74 (1994).

- Roberts J.A., Bacon R., Exploring the subtle relationships between environmental concern and the ecologically conscious consumer behavior, Journal of Business Research, 40(1):79–89 (1997).

- Lin, P. C. and Huang, Y. H.,The influence factors on choice behavior regarding green products based on the theory of consumption values, Journal of Cleaner Production, 22(1): 11-18 (2012).

- Hu, H. H., Parsa, H. G. and Self, J., The dynamics of green restaurant patronage.Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 51(3): 344-362 (2010).

- Choi, M. S. and Kim, Y., Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and PCE, Advances in Consumer Research, 32(1): 592-599 (2005).

- Van Liere, K.D. and Dunlap, R.E., Environmental Concern: Does It Make a Difference? How it is measured? Environmental and Behaviour, 13(6): 651 –676 (1981).

- Samarasinghe, G. D., and Samarasinghe, D. S. R., Green decisions: consumers' environmental beliefs and green purchasing behaviour in Sri Lankan context,International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, 7(2), 172-184 (2013).

- Fryxell, G. E. and Lo, C. W., The influence of environmental knowledge and values on managerial behaviours on behalf of the environment: An empirical examination of managers in China, Journal of Business Ethics, 46 (1): 45-69 (2003).

- Bartkus, K. R., Hartman, C. L. and Howell, R. D., The measurement of consumer environmental knowledge: Revisions and extensions, Journal of Social Behavior and Personality,14(1): 129-146 (1999).

- Stutzman, T. M. and Green, S. B., Factors affecting energy consumption: Two field tests of the Fishbein-Ajzen model, The Journal of Social Psychology, 117(2): 183-201 (1982).

- Arcury, T., Environmental attitude and environmental knowledge, Human Organization, 49(4): 300-304 (1990).

- Bazoche, P., Deola, C. and Soler, L. G., An experimental study of wine consumers’ willingness to pay for environmental characteristics. In12th Congress of The European Association of Agricultural Economics-EAAE (2008).

- Loureiro, M. L., Rethinking new wines: implications of local and environmentally friendly labels, Food Policy, 28(5): 547-560 (2003).

- Peattie, K., Green consumption: behavior and norms, Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 35(1): 195 (2010).

- Mostafa, M. M., Shades of green: A psychographic segmentation of the green consumer in Kuwait using self-organizing maps, Expert Systems with Applications, 36 (8); 11030-11038 (2009).

- Rokicka, E., Attitudes towards natural environment, International Journal of Sociology, 32(2): 78–90 (2002).

- Stern, P. C., What psychology knows about energy conservation? American Psychologist, 47(10), 1224-1232 (1992).

- Chan, R. Y. and Lau, L. B., Antecedents of green purchases: a survey in China, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 17(4): 338-357 (2000).

- Barber, N., Taylor, C. and Strick, S., Wine consumers' environmental knowledge and attitudes: influence on willingness to purchase, International Journal of Wine Research,1(1): 59-72 (2009).

- Chan, R. Y. K., Determinants of Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior, Psychology and Marketing, 18(4): 389-413 (2001).

- Cohen, M.R., Environmental information versus environmental attitudes, Journal of Environmental Education, 5 (2): 5-8 (1973).

- Flamm, B., The impacts of environmental knowledge and attitudes on vehicle ownership and use, Transportation research part D: transport and environment,14(4): 272-279 (2009).

- Aaker, D.A., Managing brand equity. Free Press, New York (2001).

- Glazer A, and Konrad K. A., signaling explanation for charity, American Economic Review, 86 (4):1019–28 (1996).

- Bennett A. and Chakravarti A.,The self and social signaling: explanations for consumption of CSR-associated products, Advances in Consumer Research, 36:49–50 (2009).

- Hirschman, E. C., Comprehending symbolic consumption: three theoretical issues in Symbolic Consumer Behavior. In Proceedings of the conference on consumer esthetics and symbolic consumption. Hirschman, EC (1980).

- Solomon M. R., The role of products as social stimuli: a symbolic interactionism perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 10 :319–329 (1983).

- Van Vugt M., Roberts G. and Hardy C., Competitive altruism: development of reputation- based cooperation in groups. In Dunbar R, Barrett L, editors. Handbook of evolutionary psychology, Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, 531–40 (2007).

- Griskevicius V., Tybur J.M. and Van den Bergh B., Going green to be seen: status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98 (3): 392–404 (2010).

- Chen, M. F., and Tung, P. J., Developing an extended Theory of Planned Behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels, International journal of hospitality management,36, 221-230 (2014).

- Mostafa, M. M., Gender differences in Egyptian consumers’ green purchase behaviour: the effects of environmental knowledge, concern and attitude, International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31 (3): 220-229 (2007).

- Hartmann, P., and Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V., Effects of green brand communication on brand associations and attitude. InInternational advertising and communication, Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag, Wiesbaden, 217-236 (2006).

- Kim, Y. and Han, H., Intention to pay conventional-hotel prices at a green hotel–a modification of the theory of planned behavior, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18 (8): 997-1014 (2010).

- Kim, Y. J., Njite, D. and Hancer, M., Anticipated emotion in consumers’ intentions to select eco-friendly restaurants: Augmenting the theory of planned behavior, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 34: 255-262 (2013).

- Fornell, C. and Larcker, D. F., Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error, Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1): 39-50 (1981).

- Nunnally, J.C., Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill, New-York, 245 (1978).

- Bagozzi, R. P., and Yi, Y., On the evaluation of structural equation models, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16 (1): 74-94 (1988).

- Compeau, D., Higgins, C. A. and Huff, S., Social cognitive theory and individual reactions to computing technology: A longitudinal study, MIS quarterly, 23(2): 145-158 (1999).

- Chau, P. Y., and Hu, P. J. H., Information technology acceptance by individual professionals: A model comparison approach, Decision Sciences, 32 (4), 699-719 (2001).